Wouldn’t a vibrant display of pollinators outside your window be amazing? Imagine the colorful wings and busy buzzing. Maybe you feel a little bit disconnected from nature right outside your door. Creating wildlife friendly landscapes can change that, bringing life and ecological benefits straight to your yard.

Helping local animals feels great, especially since their homes are getting smaller. Transforming even a small part of your garden can make a real difference for attracting wildlife. Making wildlife friendly landscapes doesn’t have to be complicated or demand a complete overhaul overnight; simple steps can yield significant results.

Table of Contents:

- Why Bother with a Wildlife Garden?

- Getting Started: The Basics

- Rethink the Lawn

- Choosing Plants for Wildlife Friendly Landscapes

- Building Habitat Features

- Garden Care That Helps Wildlife

- Nurturing Nature and People

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Conclusion

Why Bother with a Wildlife Garden?

Think about it: developments and large farms often replace natural areas. It’s a real problem: many animals are going without the basic necessities for life—food and a safe place to live. Think of your garden, or even just your balcony! Think of these small areas as animal havens. Protection and resources—that’s what makes them so important for survival. Animals need these places to thrive. Think of them as apartments in a big city for wildlife.

Animals can move safely between separated habitats thanks to these connecting natural spaces. Animals have their own expressway! Plus, a garden buzzing with activity is just more interesting and engaging. Imagine watching goldfinches splash in a bird bath or seeing native bees diligently visiting your flowers.

Think of it this way: a thriving local environment means a healthier environment for people. Supporting nature supports us. Chemical use drops when birds eat so many insect pests. Pests are controlled naturally. Bees and other bugs are super important for pollination. Wildflowers and many of our food crops depend on them. Food safety and availability are directly affected. Healthy soil is a result of nature. The soil gets a boost in fertility; water filtration also gets a boost.

Getting Started: The Basics

You don’t need a huge space or extensive gardening experience to start helping wildlife. Your local ecosystem will thrive with a few thoughtful additions. Consider adding a small pond or a compost bin to your yard. Think about the core needs all creatures share: food, water, shelter, and places to raise young.

Water is Life

One of the easiest and most effective additions is a reliable water source. All wildlife needs water, and providing it can draw animals to your yard quickly, especially during hot, dry periods. A shallow bird bath is a perfect starting point for birds needing a drink or a splash.

Keep the water shallow – birds generally prefer depths no more than an inch or two, similar to a puddle edge. A basin with a rough surface provides better grip than a smooth one. You can purchase various styles or create a naturalistic basin from a large, flat stone.

Place your bird bath near shrubs or small trees to offer cover, giving birds a quick escape route from predators. Avoid placing it directly under dense branches where cats might hide. Remember that regular cleaning and fresh water every couple of days are crucial for preventing algae and the spread of disease among visiting birds.

Small ponds or even simple container water gardens can significantly broaden the appeal, attracting frogs, toads, dragonflies, and beneficial insects. Ensure any water feature has gently sloped sides or strategically placed rocks. This allows animals like chipmunks or thirsty insects to drink safely and escape if they fall in.

Go Native with Your Plants

If you make only one change, prioritize adding native plants. These are the species that have naturally occurred in your region for thousands of years. Local wildlife, from insects to birds, evolved alongside these specific plants and depend on them.

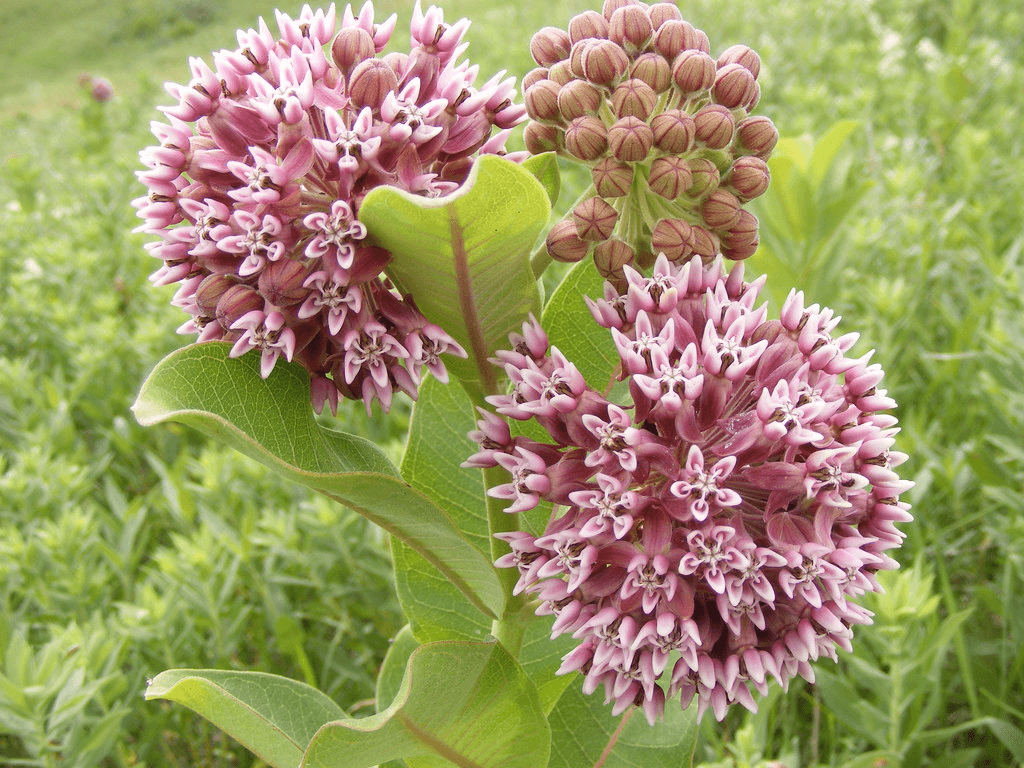

Local bugs need local plants to survive; it’s a simple food chain. Native plants are their grocery store. For instance, Monarch butterfly caterpillars exclusively eat milkweed leaves; without milkweed, Monarchs cannot complete their life cycle. You can identify plants native to your area using online resources like the National Wildlife Federation’s Native Plant Finder or local extension gardener guides.

Those little caterpillars? Baby birds really need them! Especially the ones loaded with protein. Mama and Papa bird need them to raise their young. Planting natives thus builds the foundation of the local food web. Additionally, native plants are naturally adapted to your area’s climate and soil conditions, usually requiring less water, fertilizer, and overall maintenance once established compared to non-native ornamentals.

Consulting resources from your local cooperative extension or visiting public gardens like the JC Raulston Arboretum can provide excellent native plant selection guidance. They often have display gardens and plant databases, like the NC State Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, tailored to specific regions, such as North Carolina (NC).

Rethink the Lawn

Expansive lawns of non-native turfgrass offer minimal value for most wildlife. Consider reducing the size of your lawn area. Replace portions of it with garden beds filled with native wildflowers, shrubs, grasses, or even a small dedicated meadow patch.

Even relatively small patches of native plantings provide significantly more resources—nectar, pollen, seeds, host leaves, shelter—than large areas of mown grass. A secondary benefit is reduced mowing time and effort. Smaller lawns use less water, fertilizer, and pesticides. Cleaner water and a healthier planet? This does both!

Transitioning lawn space can be gradual. Start with a small border or island bed and expand over time. Ecological function and aesthetic appeal work together in this landscape design; it’s a harmonious blend. Think vibrant flowers attracting pollinators while creating a stunning view.

Choosing Plants for Wildlife Friendly Landscapes

Careful plant selection is key to attracting a diversity of wildlife and is an enjoyable part of the process. Aim for variety in plant types (trees, shrubs, perennials, grasses) and ensure there are overlapping bloom times throughout the growing season. This provides a continuous food source and shelter options from early spring through late fall.

Creating a bloom calendar for your potential plant choices can help visualize coverage. Choose plants that offer beauty throughout the seasons. From springtime blossoms to autumn’s fiery colors, and even winter interest, there are many options to explore. Year-round food and habitat? Plant smart!

Mighty Trees as Anchors

Trees form the structural backbone of many wildlife habitats. Native oaks are super important for the environment. Depending on the region, a single mature oak can support hundreds of species of moth and butterfly caterpillars, which are essential bird food, especially during nesting season.

Research which oak species are native to your specific area before planting. Beyond oaks, many other native canopy trees offer significant wildlife value; consider maples, birches, or hickories suitable for your climate and available space. Even one or two strategically placed native trees can make a substantial difference in attracting wildlife.

Don’t overlook smaller native understory trees and large shrubs that bear fruit. Serviceberries (Amelanchier), native dogwoods (Cornus florida), American persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), or pawpaws (Asimina triloba) provide flowers for pollinators, leaves for caterpillars, and fruit (a critical food source) for birds and mammals. They’re pretty to look at, these plants.

Create Layers for Shelter

Natural environments are rarely uniform; they consist of multiple vertical layers. Mimic this structure in your garden by incorporating plants of different heights. Combine tall canopy trees, smaller understory trees, shrubs of varying sizes, and layers of herbaceous perennials, wildflowers, and groundcovers.

Creating layers in your yard’s landscaping produces little pockets of different habitats. Birds might nest high in trees, forage for insects among shrubs, and find seeds or shelter near the ground. Animals feel safer because the complicated structures offer shelter from both predators and bad weather.

Consider planting combinations like a native maple tree, beneath it some flowering dogwood or viburnum shrubs, and below those, shade-tolerant ferns, wildflowers like foamflower (Tiarella), or native groundcovers. Wildlife benefits, and the landscaping looks better. Thoughtful arrangement of shrubs can create protected nest sites.

Birds and people both enjoy berries.

Let’s plant some berry bushes; imagine all those pies! They’ll give birds food, and you’ll have a beautiful yard. This is especially helpful in the late summer, fall, and winter. Focus on native species like elderberry (Sambucus canadensis), winterberry holly (Ilex verticillata), chokecherry (Prunus virginiana), beautyberry (Callicarpa americana), or various native viburnums. Lots of these bushes have pretty flowers that bees and butterflies love before the berries or fruit appear.

You can plant these berry-producing shrubs as individual specimens within mixed borders or create a denser thicket or grove if space allows. A dense patch offers superior cover along with an abundant food source. Position these plantings where you can easily observe the birds enjoying the fruits of your labor.

Vines Climb High

Maximize habitat, especially in smaller gardens, by utilizing vertical space. Native vines can climb fences, trellises, arbors, or even scramble over walls and rock piles. It’s like getting more room, but without taking up a big footprint.

Trumpet honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens), a native species distinct from the invasive Japanese honeysuckle, is a fantastic choice for attracting hummingbirds with its tubular red flowers. Other valuable native options include native clematis species, passionflower (Passiflora incarnata, a host plant for fritillary butterflies), or Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), which offers fall color and berries for birds. Always verify which vines are native and non-invasive in your specific region before planting.

Flowers for Pollinators

Bees, butterflies, moths, hummingbirds, and even some beneficial flies and beetles depend on nectar and pollen from flowers for energy and reproduction. Plant a wide assortment of native flowers with different shapes, colors, and sizes that bloom sequentially from early spring until late fall. We have a steady food supply, no matter the season.

Include various native milkweeds (Asclepias species) in your plantings; they are the essential host plants for Monarch butterfly caterpillars. Flowers with flat-topped structures, like native yarrow (Achillea millefolium), Joe Pye weed (Eutrochium purpureum), or goldenrods (Solidago species), provide convenient landing platforms for many insects. Think about it: long, thin flowers? Hummingbirds and long-tongued bees love them! The way a flower looks directly influences which animals will pollinate it. Think of it like a key fitting a specific lock.

Consider adding native grasses too, like little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) or switchgrass (Panicum virgatum). Winter survival for many insects depends on these plants. Just like us, birds and bees require food to survive and materials to make their homes.

Below is a table summarizing some plant types and the wildlife they support:

| Plant Type | Examples (Native Focus) | Wildlife Supported |

|---|---|---|

| Canopy Trees | Oaks (Quercus spp.), Maples (Acer spp.), Birches (Betula spp.) | Caterpillars (bird food), Nest Sites, Shelter, Acorns/Seeds |

| Understory Trees / Large Shrubs | Dogwood (Cornus spp.), Serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.), Viburnum spp. | Flowers (Pollinators), Berries (Birds/Mammals), Nest Sites, Host Plants |

| Shrubs | Elderberry (Sambucus), Winterberry (Ilex verticillata), Beautyberry (Callicarpa) | Berries (Birds), Shelter, Nest Sites, Flowers (Pollinators) |

| Vines | Trumpet Honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens), Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus) | Nectar (Hummingbirds/Insects), Berries (Birds), Shelter, Host Plants |

| Flowers / Perennials | Milkweed (Asclepias), Coneflower (Echinacea), Goldenrod (Solidago), Aster spp. | Nectar & Pollen (Pollinators), Seeds (Birds), Host Plants (Insects) |

| Grasses | Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium), Switchgrass (Panicum), Indiangrass (Sorghastrum) | Seeds (Birds), Nesting Material, Overwintering Habitat (Insects), Host Plants |

Building Habitat Features

Beyond plants, you can incorporate non-living elements that significantly enhance your yard’s value as wildlife habitat. Harsh weather and hungry predators are no match for the safety these features offer; they provide shelter, nesting sites, and places to hide. Good landscape design considers these elements alongside plant selection.

The Simple Brush Pile

Have branches, twigs, or plant stalks accumulated after pruning or garden cleanup? Instead of discarding them, create a brush pile in an out-of-the-way corner of your yard. This easy-to-understand system is packed with great resources; you’ll find everything you need here.

Layer larger, sturdier branches on the bottom to create spaces, then pile smaller twigs and stems loosely on top. Think of all the animals that benefit! This structure shelters ground-feeding birds (sparrows and towhees, for example), small mammals (like chipmunks and rabbits), and a surprising number of reptiles, amphibians, and beneficial insects. This small area is teeming with wildlife; it’s amazing! Predators and bad weather? No problem here! Here, you’ll be protected from harm; this is a sanctuary.

Rock Piles and Logs

Strategically placing rocks or logs can also create important microhabitats. A small pile of rocks, perhaps integrated into a garden bed or border, offers crevices and hiding spots for insects, spiders, salamanders, small snakes, or even chipmunks. A decaying log, especially one partially buried, provides shelter, supports fungi and decomposing insects (which become food for other animals), and slowly enriches the soil fertility.

The garden’s texture and visual appeal are boosted by these features, giving it the complexity of a natural meadow or forest. The habitat is more complete because of them. These really complete the picture. Make sure rock piles are stable and won’t easily tumble.

Welcoming Ponds and Pools

If you have adequate space and are willing to maintain it, adding a small pond or water garden dramatically increases the habitat value of your yard. Even a tiny, well-maintained water feature reliably attracts dragonflies, damselflies, frogs, toads, and salamanders. Birds will also frequent ponds for drinking and bathing.

Ensure the pond has gently sloping sides or incorporates rocks and logs to allow creatures easy access to the water and a safe way out if they fall in. Incorporate native aquatic and marginal plants like rushes, sedges, pickerelweed, or water lilies around the edges for cover and egg-laying sites. Avoid introducing fish into very small ponds, as they often consume amphibian eggs and larvae, undermining the pond’s value for supporting amphibian populations.

Making a Mini-Meadow

You don’t need acres of land to enjoy the benefits of a meadow; even a small area can be converted. Replacing a section of lawn, perhaps 5 by 10 feet or larger, with a mix of native grasses and wildflowers creates a vibrant, low-maintenance habitat patch. This patch will buzz with life compared to the surrounding lawn.

Proper site preparation is crucial for success; this usually involves completely removing the existing turf grass and its roots. Once the site is prepared, you can sow a regionally appropriate native seed mix or plant plugs (small starter plants) of native meadow species. This gardening method looks and works differently than the usual garden beds.

Mini-meadows attract a wide array of butterflies, bees, beneficial insects (predators of pests), and seed-eating birds like finches. Once established, they typically require less ongoing maintenance than a manicured lawn, often needing only an annual mowing (timed to avoid disrupting nesting birds or overwintering insects). Research appropriate meadow creation techniques and seed mixes recommended by your local cooperative extension or native plant societies.

Garden Care That Helps Wildlife

How you maintain your garden is just as crucial as the plants and features you install. Some common garden care practices can inadvertently harm the very creatures you’re trying to attract. A healthier landscape is easy to achieve with some simple improvements. Consider new methods today!

Avoid Pesticides and Herbicides

Synthetic chemical pesticides are designed to kill insects but are often indiscriminate, killing beneficial insects like pollinators (bees, butterflies) and pest predators (ladybugs, lacewings) along with the target pests. Herbicides kill plants designated as weeds, but many native “weeds” are actually vital food sources (providing seeds or nectar) or essential host plants for specific insects. The insects are poisoned, the birds that eat them are poisoned, and the whole food web is affected by these toxic chemicals contaminating our soil and water.

Adopt a higher tolerance for imperfection in your garden. Accept minor pest damage on plants and learn to identify common native plants that might appear weed-like but offer ecological value. Employ integrated pest management (IPM) techniques, which prioritize prevention, monitoring, and using the least toxic controls only when necessary. Healthy, diverse gardens built on good soil fertility are often naturally more resilient to pests and diseases, requiring less intervention for managing insects and managing diseases.

Focusing on prevention through smart plant selection and placement, promoting beneficial insects, and improving soil health are cornerstones of IPM. Familiarize yourself with pesticide safety if chemical use is unavoidable, but always seek alternatives first. Weed control is best done by mulching, pulling weeds when they’re small, and stopping weed seeds from spreading. Herbicides aren’t the only answer.

Embrace Composting

Composting kitchen scraps (vegetable matter, coffee grounds) and yard waste (leaves, grass clippings, plant trimmings) transforms waste into a valuable resource. Supercharge those garden beds: grab some free compost! It’s amazing soil amendment. Composting shrinks the amount of organic trash going to landfills. Landfills produce methane, a serious greenhouse gas, as organic matter breaks down without oxygen.

Compost helps your soil; it improves drainage, lets air in, and holds onto water better. Healthier plants mean you water them less often. Compost-rich soil is a dynamic ecosystem. Plants grow best in soil teeming with life. This includes the easily seen insects and worms, but also the microscopic communities of microbes that are essential for healthy growth. The more diverse the soil life, the better the plants will thrive.

Leave the Leaves

In the fall, resist the ingrained habit of raking, blowing, and bagging every fallen leaf. Leaf litter on the ground is not waste; it’s a vital natural habitat layer. Many species of butterflies and moths overwinter in the leaf litter as eggs, caterpillars, pupae (in chrysalises or cocoons), or even adults.

Fireflies, queen bumble bees, salamanders, spiders, millipedes, and countless other beneficial invertebrates also depend on the insulating blanket of leaves for survival through the winter. Raking leaves onto your garden beds acts as a natural mulch, suppressing weeds, retaining moisture, and slowly enriching the soil as they decompose. Alternatively, maintain a designated “leafy” area in a less visible part of your yard to provide this crucial overwintering habitat.

Consider Outdoor Lighting

Excessive artificial light at night disrupts the natural world in numerous ways. Bright overnight lighting can interfere with the navigation, feeding behaviors, and mating rituals of nocturnal animals, particularly moths (important pollinators and food source) and fireflies (whose populations are declining). Migrating birds get disoriented by artificial lights. This can lead to them getting lost or hitting buildings.

Where possible, minimize the use of unnecessary outdoor lighting. For security purposes, consider using motion-sensor lights that only turn on when needed, rather than staying on all night. Choose lighting fixtures that are downward-shielded, directing light onto the ground where it’s needed and preventing light pollution into the sky and surrounding habitats. Opting for warmer colored bulbs (yellowish or amber tones) tends to be less disruptive to wildlife than bright white or blueish lights.

Wildlife management includes reducing impacts from human-caused light and noise pollution; these disturbances can significantly impact animal habitats and behaviors. Artificial lights mess with how night animals eat, and too much noise stops them from talking to each other and having babies. Thoughtful lighting choices contribute significantly to wildlife friendly landscapes.

Nurturing nature is a way to support people, and vice versa. Planet health is directly tied to human health. It’s a simple connection.

People connect with nature when we create these spaces; it’s good for the planet, too. Engaging in gardening and observing the visiting wildlife can reduce stress and provide a sense of accomplishment. The activities work well with what garden therapy is all about.

Imagine using a wildlife garden as your classroom—how cool would that be? Youth gardening programs get a boost, furthering the aims of the natural learning plan. Direct observation of insects and birds—like watching a caterpillar turn into a butterfly or a robin build a nest—is incredibly educational for young children. Hands-on experience? Priceless.

For those interested in deepening their knowledge, resources like the extension gardener handbook or other gardening publications from the cooperative extension offer detailed guidance. Attending workshops or even participating in travel study adventures focused on ecology or horticulture can provide further inspiration. Many public gardens teach classes on related subjects; these classes don’t give college credit.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Exploring wildlife friendly landscapes often brings up common questions. Need a hand? These answers to frequently asked questions will help you get going or polish your plan. Having answers to frequently asked questions can make the process smoother.

Q: Do I need a large yard?

A: No, even small spaces like balconies or patios can support wildlife. Use containers to plant native flowers for pollinators or provide a small water dish. Every bit helps.

Q: Will attracting wildlife bring pests?

A: A diverse native planting actually attracts beneficial insects that help control pest populations naturally. Skip the pesticides; you’ll help beneficial insects thrive. Healthy ecosystems tend to keep pest populations in balance.

Q: Locating plants indigenous to your specific geographic location requires a bit of research, but the payoff is well worth it. Consult online databases or your local agricultural extension office.

A: Use online tools like the National Wildlife Federation’s Native Plant Finder or Audubon’s Plants for Birds database. Contact your local cooperative extension office; they often provide lists and resources like the NC State Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox for residents of North Carolina. Native plants? Your local nursery is the place to go.

Q: What if deer eat my plants?

A: Managing wildlife like deer can be challenging. Look up plants native to your area that deer don’t like to eat. Fencing may be necessary for certain areas, or you can use repellents, although their effectiveness varies. Focusing plantings closer to the house sometimes deters deer.

Q: Is it safe to have wildlife close to my house?

A: Generally, yes. Most garden wildlife poses no threat. Avoid leaving out pet food that could attract unwanted visitors like raccoons or rodents. Child and pet safety starts with knowing your local poisonous plants. Take some time to learn how to identify them; it could save a life.

Conclusion

It’s a continuous process to create landscapes that benefit wildlife; think of it like gardening—always growing and changing. The reward? Think about it: this is serious. I’m blown away by the sheer size of it. Prepare to be amazed. Begin with manageable steps, perhaps adding a bird bath, planting a few native shrubs, or dedicating a small patch to native wildflowers. Observe the results and add more elements as your time and resources permit.

Note the animals drawn to your developing habitat; understanding their specific requirements is crucial for its success. For example, are there enough food sources, appropriate shelter, and safe spaces for nesting or raising young? Imagine the satisfaction: your yard, a vibrant hub of local biodiversity. Creating a successful natural habitat? Pure magic. Connecting with nature is easy. Just add a little bit of it to your space, and watch your surroundings improve. It’s a win-win: you help the planet! Enjoy the journey of building your wildlife friendly landscapes.